If one searches “Casarabe Culture” in a search engine, they won’t find much. Maybe they will see a Wikipedia article for the town of Casarabe in Bolivia less than 10 words long.

However, a paper published today in Nature reveals that down in an alluvial plane in Bolivia’s Llanos de Mojos savannah in southwest Amazonia, flourished an agrarian low-density urban society for 900 years, building hundreds of hectares of monumental earthworks, canals, walls, and fortifications, and large pyramids.

The Casarabe culture transformed and lived off the land in a way few archeologists and historians believed possible for the Amazon. The sparsely populated region in the north of Bolivia has suffered little disturbance over the years, and since 1960 archeology has known that extensive evidence of earthworks was to be found in the plane—everything from causeways and mounds to potential artificial islands.

However after working in the area for 20 years, archeologist Dr. Heiko Prümers led a LIDAR survey to get an idea of the total extent of the civilized area, and has revealed details of a major continental civilization that grew maize and yuca equal to and exceeding at times the size and efficiency of similar areas in Medieval Europe.

“It’s a very important step that we made right now: that we can show to other people that we have got there something in the Amazon region that nobody expected, but that we know existed,” says Prümers.

“Now it’s obvious that this region of the world like many other tropical regions, like Mexico, or Angkor in Cambodia or some cities in Sri Lanka that are located in tropical regions, they are not the “green deserts” that have been imaged for a long time”.

Tree-scrubbing

For two reasons, an established orthodoxy led archeologists to believe that the Mayan Civilization was uniquely exceptional among tropical forest-dwelling Mesoamerican societies. The first is the immense scale of the Mayan cities, and the second is the well-known fact that tropical soils are poor for any kind of centralized food production.

Okay, so the famous calendar makers aside, the old orthodox still applied for years to people further south, in Amazonia, where even poorer conditions left them imagined as simple subsistence farmers of little societal, or technological development.

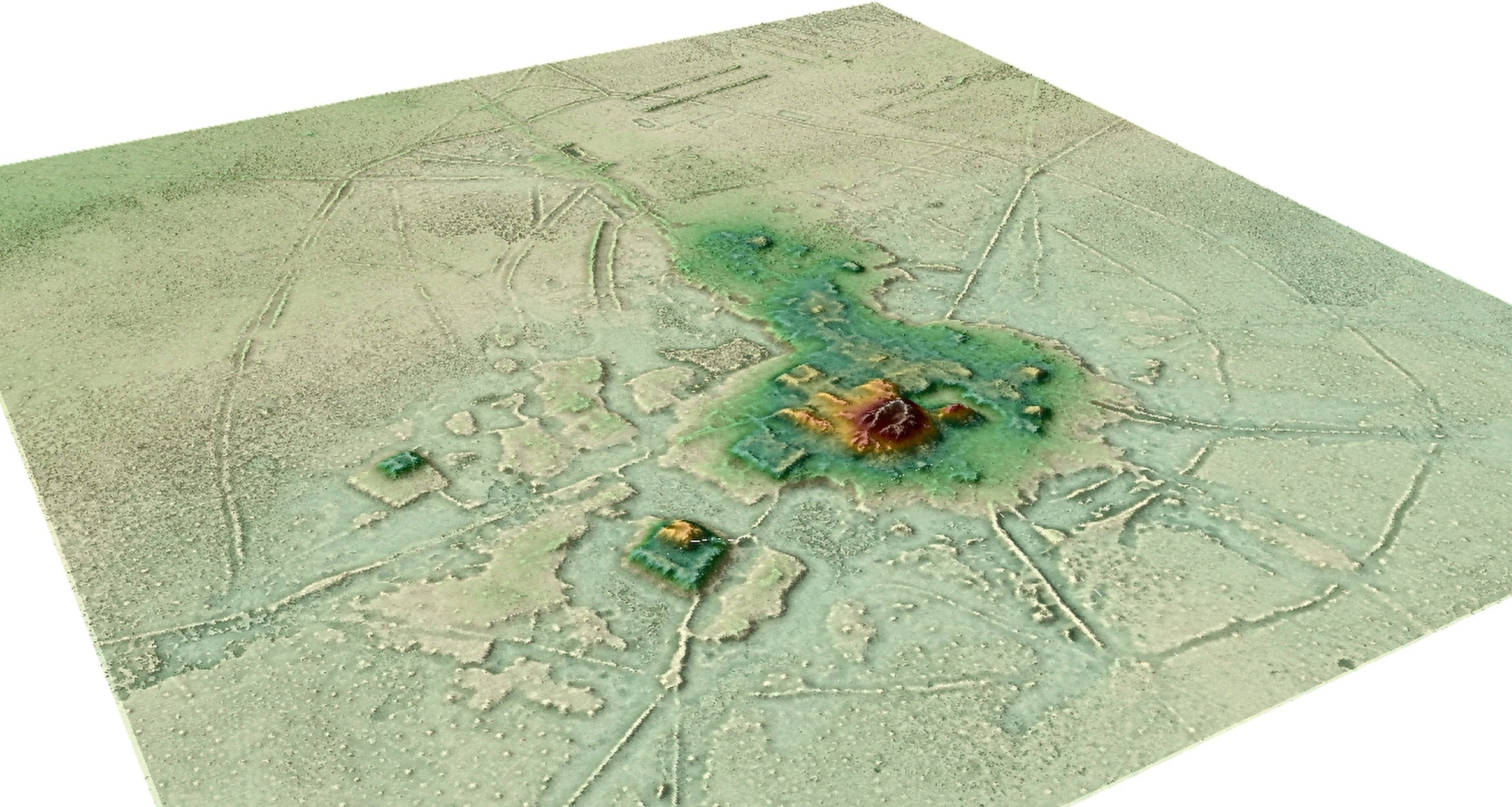

With LIDAR (light-detection and ranging) Prümers et al. were able to map the precise contours of a 204 square kilometer piece of land without any interference from the trees or marshes, effectively scrubbing away anything that would impede the vision of a satellite photo. What was revealed were 24 sites, roughly half of which were unknown, all built of raised earthen mounds, including two remarkably large sites of 147 and 315 hectares each.

“The scale of the architectural remnants at these sites, which include earthen pyramids that once towered more than 20 meters over the surrounding savannah, cannot be overstated and is on a par with that of any ancient society,” wrote Christopher Fisher, a geo-anthropologist at Colorado State Univ. Fort Collins, who wasn’t involved in the study.

The civic-ceremonial architecture of these large settlement sites, called Cotoca, and Landivar, includes stepped platforms, on top of which lie U-shaped structures, rectangular platform mounds, and conical pyramids up to 22 meters tall.

Extending out in a 500 square kilometer area from the center of Cotoca, long straight causeways connected various raised mounts of smaller scope, suggesting that Cotoca’s urbanism sprawled about, but was slightly contained by, the low-lying watered ground.

“All these settlements are embedded in a human-engineered landscape with a massive water-control system designed to maximize food surpluses to support the large Casarabe population,” writes Fisher.

Who were the Casarabe?

Known to have existed down in Llanos de Mojos from 500 CE to 1400 CE, the Casarabe culture takes its name from a modern-day town near to where the sites like Cotoca and Landivar were first found. They were chiefly agriculturalists, and also great movers of earth.

“At the same time the Casarabe developed we have in the Andes the culture of Tiwanaku, a very big imperium that stretched from the Chilean coast to La Paz in Bolivia,” Dr. Prümers explained to WaL in an interview.

“That’s one of the intriguing things we have to resolve in the future,” he said, noting the lack of evidence for contact between Casarabe and Tiwanaku. “Of course there must have been a relationship in some context, but in the archeological record there’s little evidence of that”.

“They’re not hunter-gatherers like some people have maintained until now. They cultivated maize, yucca maybe, so I think we must imagine a type of culture just like in Europe at that time, with the same kind of villages and small cities. Cotoca would very much be the same as a Medieval city of that time in Europe – it’s walled, it has a core area with administrative and ceremonial purposes”.

“We are lucky in the sense that this region is very poorly populated in the last 900 years, so there’s been very little modern disturbances,” says Prümers.

“Just imagine you are working 20 years in that region like we did, and you have to explain to someone not familiar with the archeology of the region, and they’re asking what is special about that culture—you’d need an hour to explain it,” he said. “Now we just show the images, and everybody will say ‘wow, yes it’s obvious that it’s something big’”.

The moving of earth to create these structures was remarkable, and on par with some of the greatest earth-moving societies of the period. The central cityscapes of Landivar and Cotoca were built on a raised platform assembled in Landivar’s case by moving 275,000 cubic meters of soil, and in Cotoca’s with roughly 570,000 cubic meters of soil, about ten times as much as was moved to create Akapana, a similar site in Tiwanaku.

Of comparisons, there is only one — Cahokia, the pre-Colombian city-state in Missouri which built raised earthen mounds totaling into the millions of cubic meters.

“Cahokia is a very good example to compare with, especially the history of the investigation; because for a long time it was dispelled as the idea of an important [regional center,] now we know that it was, and it’s one of the largest structures ever constructed in the New World,” says Prümers. “The Cotoca site is not as huge as Cohokia, but it’s not so far away”.

As notable as the massive moving of earth is the complete lack within the Casarabe archeological record of any kind of widespread evidence of stones. They must have had some, but only for making small tools. Dr. Prümers explains.

“During our excavations in almost 10 years, maybe we’ve found one or two kilos of stone, and that stone was imported from the Andes!” he said.

Uncertain future of the Casarabe site

All work on the sites was done with a more-or-less consenting local population, but even though modern archeology generally requires consent from indigenous people before something like an excavation can begin on a site historically relevant to them, Dr. Prümers would explain to WaL that it’s not as simple as going to the Bureau of Indian Affairs and filing paperwork.

“We didn’t call it a collaborative project, but of course all our work is run from the neighboring village called Casarabe,” Prümers said. “They took a lot of interest in our work and I think it’s one of the best ways to incorporate them and show them their own history but the problem is that there’s no intuitions that protect the heritage”.

“The problem is that people in that department are not very interested, there’s a lot of detraction going on. Most of the sites are lying on private property and the people won’t respect anything. If you tell them it’s patrimony and that it’s protected they will be even more tempted to destroy it because they fear the state will take the land away from them”.

“It’s a dilemma. Some of the sites were were unable to investigate because people wouldn’t let you go, because of that fear that somebody will tell them it’s an archeological site, it’s protected by law,” he said. “The indigenous population are well-informed and involved in the project, well, by us”.

It’s fascinating to think that these earth-moving corn farmers would survive 900 years, more than 3 times as long as the current American culture. It clearly wasn’t just large earthworks they built, but a strong enduring foundation, which is now up to people like Prümers to try and preserve into the ages.WaL

PICTURED ABOVE: A 3D image of the LIDAR survey showing conclusively that an urban-agrarian culture in the southern Amazon was capable of sophisticated engineering, irrigation, and societal organization. PC: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Bonn, courtesy of Heiko Prümers.

If you think the stories you’ve just read were worth a few dollars, consider donating here to our modest $500-a-year administration costs.