The next great era of paleontology may not actually happen digging in the field, but rather digging through drawers.

Of museum collections, specifically. This summer has seen a raft of stories about lost or misidentified dinosaur fossils being pulled out of museums, rather than rock formations. Decades of technological innovation and taxonomical recalibrations offer the chance to better classify or identify species that had been discovered years ago but were either forgotten about or mislabeled.

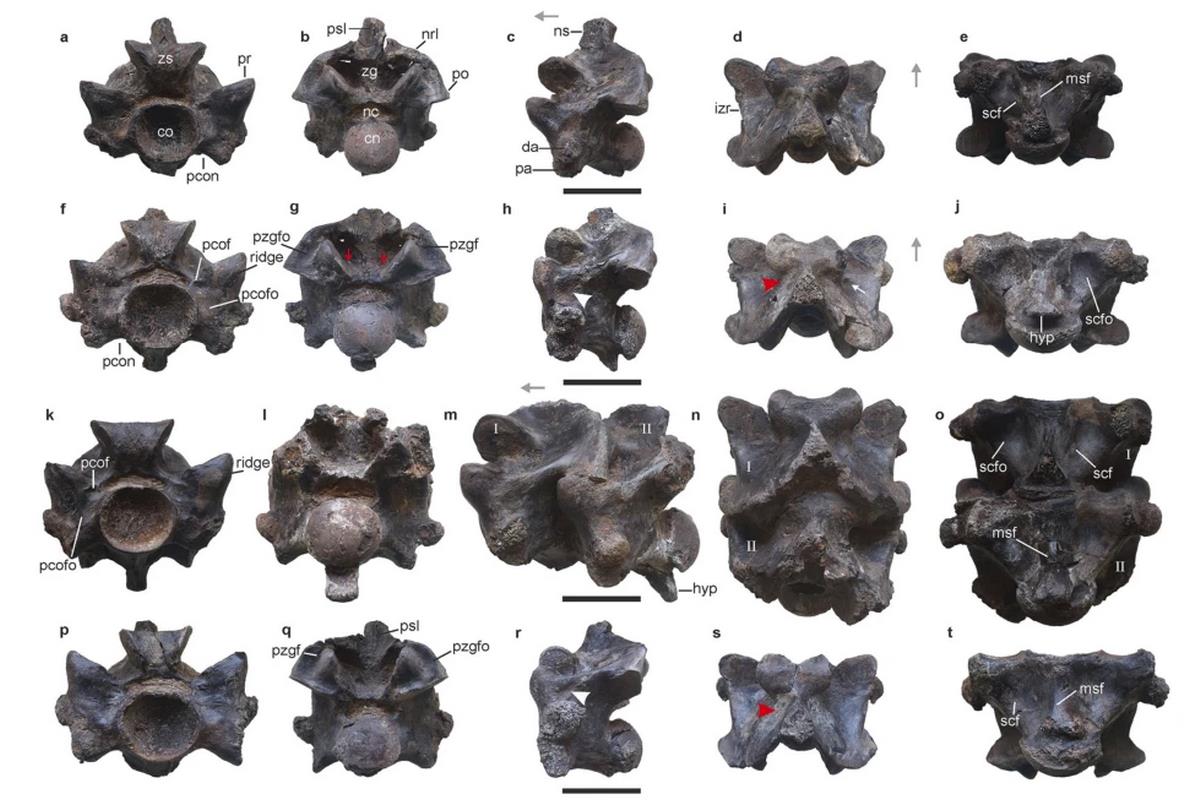

A case in point would be a story from Mongolia, where the newly-dubbed “Dragon Prince of Mongolia”—a key member of the Tyrannosaurid lineage, was found buried in a museum archive for 50 years. Pulled out of a drawer and reexamined by Ph.D. student Jared Voris from the University of Calgary, it had been sitting in the Mongolian Academy of Sciences since the 1970s, having been labeled an Alectrosaurus.

Professor Darla Zelenitsky, the lead author of the paper describing the new animal, foresees many new discoveries coming out of museum collections in the same manner.

“It is quite possible that discoveries like this are sitting in other museums that just have not been recognized,” Zelenitsky said in an interview with AFP.

Weighing approximately the same as a large horse, this smaller tyrannosaurid lived around 86 million years ago under the shadow of much larger therapods. However, it’s presence in Mongolia offers scientists a key insight into the “really messy” history of the most famous dinosaur family.

Then, in late June, the London Museum of Natural History released a statement explaining that a dinosaur acquired for their collection has been identified as a totally new species, having previously been put in something like a “wastebin taxon” some 120 years ago when it was discovered in North America.

Put up for auction as a Nanosaurus, a species that was first found in 1877 and never well-documented, it was acquired by the museum in 2021. The following years of study revealed it to be an unknown species. Today, it’s called Enigmacursor or “mystery runner”.

A wastebin taxon in biology refers to a genus or subfamily into which lazy or perplexed biologists in the past have placed species they weren’t able to properly identify. Nanosaurus was certainly one of these, as museum professor Susannah Maidment, who co-led the examination into Enigmacursor, said in a statement.

“When Nanosaurus was named in 1877, there weren’t that many named dinosaurs so the few characteristics that its fossils preserved would have been unique”.

“Now, however, we have found hundreds of small dinosaurs from all over the world and know that the fossils of Nanosaurus just aren’t that useful, let alone enough to name a species with. As a result, it made sense to put them to one side and name Enigmacursor as a new species instead,” she said.

“Mining the basement”

These sorts of discoveries are not a new phenomenon, but rather a well-established paleontological research method called “mining the basement”.

“Poking around a collection with fresh eyes often yields exciting results,” said Dr. Scott Persons, an assistant professor and museum curator at the College of Charleston, who wasn’t involved in either discovery.

“It is very common for museums to have a backlog of collected material that no one at the museum is currently working on. Or for a museum to have lots of specimens that were collected and cataloged decades ago, but which no one has taken a close look at, recently,” he told WaL. “I remember once looking at the hipbone of an armored dinosaur and suddenly realizing it had bite marks from a tyrannosaur! In over 20 years, no one had noticed the marks before”.

“Mining” can also be done in the front of house, as was demonstrated in yet another museum mix-up at the London Museum of Natural History.

“Ph.D. student Victor Beccari couldn’t shake the feeling he had seen the fossil before: it was a slab of rock containing the impression of a Jurassic-period reptile housed at the London Natural History Museum,” Good News Network reports. He realized that same day why he had the feeling—a museum in Stuttgart had the same exact thing.

“Beccari followed his instincts and confirmed that each museum contained a half of the whole: one had the fossil, and the other the imprint it made on the prehistoric sediment”.

The discovery was not only a labeling error, as the fossil came to be recognized as a new species, but it was also a case of yet another problem that can plague museums: deceit.

“It seems that someone in the 1930s decided to double their profit by selling both halves separately,” Beccari said in a museum statement. “As they didn’t tell either buyer that there was another half, the connection between the two fossils had been lost until now. These kinds of fossils are normally preserved flat, so when they’re split open you often get the skeleton in one half and the impression of the skeleton in the other”.

What he discovered was Sphenodraco scandentis, an ancient tree-dwelling lizard previously labeled Homoeosaurus maximiliani. It appears to be the earliest tree-living rhynchocephalian ever discovered. The findings of the study, published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, reveal important elements of these animals which lived 145 million years ago.

These reptiles are actually not true lizards, but Earth’s third major reptile order alongside snakes and lizards. A little like the famous Gingko tree, there is one solitary survivor of this order today called the tuatara. It lives in New Zealand and looks much like any other lizard, but varying body sizes of extinct rhynchocephalians show that different species had a wide range of different lifestyles, shapes, and sizes.

Members like Pleurosaurus had long bodies with long back legs and short front limbs, so they are thought to have been marine reptiles. Other species had long limbs good for running, while those with a shorter body were probably climbers.

Dr. Persons, who had heard of the story, said that museum mining isn’t all about organizational mistakes but a result of scientific advancements.

“As we learn more about dinosaurs, we get better and better at telling different species apart and at figuring out what anatomical clues indicate that one set of bones belongs with another,” Dr. Persons said. “Imagine if I gave you a handful of pieces from two different sections of the same jigsaw puzzle. You wouldn’t necessarily know they go together. But as our scientific understanding of dinosaurs advances, it’s like we start to see the picture on the box cover”.

He added that it’s highly probably more of these discoveries will be made in the future, and that the rate will increase as well. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: The new species has been named Khankhuuluu mongoliensis, or Dragon Prince of Mongolia. PC: provided to the BBC by Darla Zelenitsky.