Arab-world news reports suggest that upcoming September elections in Syria aren’t all that previously-hopeful Syrians had envisioned amid the euphoria of Assad’s ouster from the country earlier this year.

With Damascus under the control of an al-Qaeda affiliate and commanded by a former “emir” of ISIS, reconstruction of the sociopolitical and ethno-religious landscape of one of the Middle East’s most cosmopolitan regions was never going to be rapid. Already thousands of Alawites have been killed in extrajudicial state violence, perhaps 1,400 have been killed in conflicts between Damascus and the southern Druze religious minority, and now violence has broken out between the capital and the largest and best-organized of Syria’s minorities, the Kurds.

In this climate, where Israeli forces raid into the country’s south and bomb Damascus with impunity, the new constitution, drafted by the ruling Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) government, will be tested in the first edition of post-Assad elections.

According to the newly-created elections commission, the democratic process will be conducted through “election and selection” referring to the executive’s power to appoint one-third of the new People’s Assembly.

“It is worrying that [a] third of the seats will be assigned by the interim president himself, while an electoral college in each province in Syria will vote for the elected seats,” Razan Rashidi, executive director of The Syria Campaign, a both in-situ and ex-situ advocacy and human rights advocate, told Middle East Eye.

Each college will include 50 people who would then elect between them a member of parliament. Average voters would, in fact, be voting for a person to vote for a parliamentarian, who would then be able to vote on laws, a process that calls into question with considerable uncertainty what chance any individual voter has of seeing their wishes carried out.

According to the election commission, this approach is intended to suit the transitional and legislative—not representative—nature of the new parliament due to the lack of infrastructure, such as reliable census data and voter registration to conduct direct elections.

The current constitution is an interim constitution, and the elections, set to take place from September 15th to September 20th, will elect an interim People’s Assembly. However, others speaking with Middle East Eye detect power grab-like elements in the structuring of the elections.

Perhaps, given the origin of the ruling regime as stateless jihadists enforcing brutal Sharia law in northwestern Aleppo, it shouldn’t come as a surprise, but HTS has given extensive international assurances that human rights, the rule of law, and democracy will be the order of their nation. The country is in desperate need of international aid and assistance following years of a brutal, fundamentalist sanctions regime on the Assad government by the United States. Any suggestion that a return to a similar totalitarian order might be on the cards would seriously endanger the substantial strides HTS has made in gaining international recognition.

Reintegration delayed by previous violence

Following the violence between Druze and government-sponsored irregulars in the country’s Suweida governate, Kurdish officials and SDF leaders have postponed discussions on how to integrate the SDF into the Syrian state military structure. Those talks were fixed for July 24th in Paris, but have been called off.

In March, the former ISIS emir and Syria’s Interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa, and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi signed a deal to incorporate Kurdish institutions into the Syrian state.

Pressure lies heavy on the autonomous Kurdish authorities to disarm and reintegrate, both by Turkiye and the US, but Kurdish officials want the SDF to remain under Kurdish control and fight as a separate body from the HTS-led Damascene military.

“The lack of a transparent military structure in Syria, especially following violence in Alawite regions on the coast and in the southern Druze-majority province of Suwayda, complicates the possibility of integrating the SDF into its military structure,” Kurdish Foreign Relations Co-Chair Elham Ahmad said in late July according to The Cradle.

The March agreement didn’t expressly include a disarming of the SDF, but it’s a condition that Damascus views as non-negotiable.

“Disarmament is a red line. We are not bargaining over our principles,” said the SDF Media Center Director Farhad Shami in an interview, adding that “the SDF seeks to engage Damascus as an equal partner, not as a subordinate”.

“No one is surrendering in Syria. Those betting on our capitulation will lose—the tragic events have made that clear,” he added, referring to the violence in Suweida.

In response, the HTS government denounced Kurdish and SDF authorities for attempting “a manipulation of public opinion”. Having killed nearly 3,000 minorities already, the government ironically accused the Kurds of trying to hold negotiations “under the threat of weapons”.

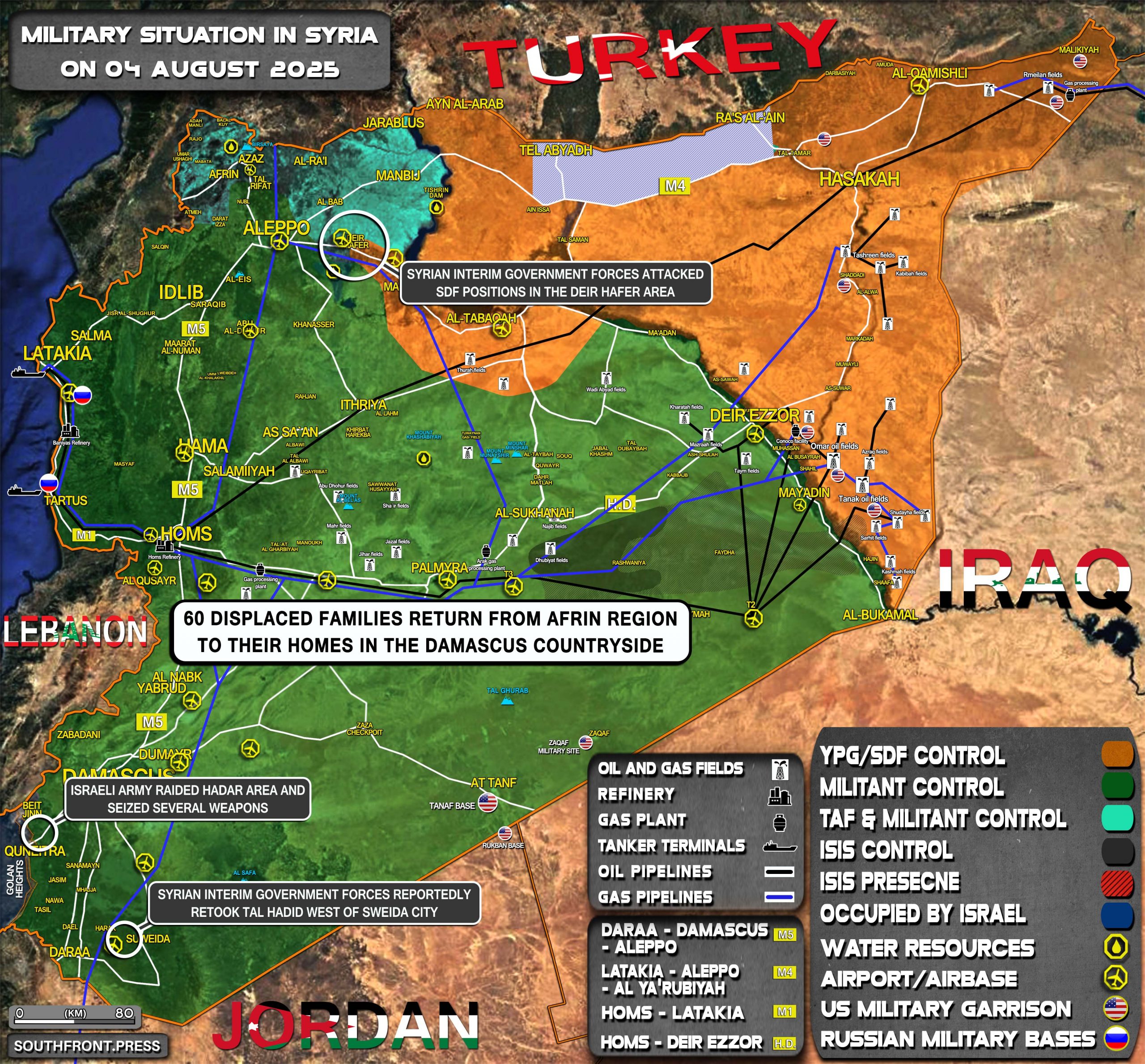

Then, on Monday, clashes broke out between SDF and Damascus-controlled forces, the Kurdish outlet Rudaw reported, after the latter “launched an attack” on four SDF positions in Deir Hafer in Aleppo province.

“Our forces confronted the attack and responded as necessary in defense of our positions and fighters. Clashes ensued and continued for 20 uninterrupted minutes,” a spokesperson for the SDF said. Regime officials put the blame solely on the Kurds, and said they had the right to respond with “with full force and determination”.

Turkish interests

As WaL reported previously, north of Syria in Turkiye, a 45-year insurgency has just ended after a Kurdish terrorist group called the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) agreed to disarm and dissolve. The news was greeted as era-ending in Ankara, while the ruling regime of President Recep Erdogan, which considers the Syrian Kurdish SDF to be closely connected with the terrorist PKK, see it as a substantial opportunity to secure political power and border security in a way that hasn’t been possible for decades.

Unsurprisingly then, Turkish authorities have strongly urged the SDF to disarm and integrate with the HTS regime in Damascus, aiding negotiations when they can, and calling for peace following Monday’s outbreak of fighting.

During the Syrian Civil War, SDF forces routinely came into contact with the confusingly named SNF—a group of Turkish-sponsored militants who have since been folded into the new state military. Without the SNF to check the American-backed SDF’s regional influence, Turkiye’s position would best be secured if the Kurds were to disarm and meld with Damascus.

Turkiye quickly established strong relations with HTS and al-Sharaa following his seizing of the capital. Erdogan’s political party holds strong Sunni Islamic principles, and analysts generally presume that Ankara believes it can turn Damascus into something of a satellite state. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: Interim-President Ahmed Al-Sharaa, receives the final version of the temporary electoral system for the People’s Assembly. PC: Office of the President of Syria, via X.