Following a veto from the Russian Federation, the strict sanctions policy on North Korea that was set to be extended into a 19th year is now set instead to elapse.

Arguments from the Russian representative were that the situation on and around the Korean Peninsula has “changed fundamentally” in recent years, and that the sanctions regime the Council adopted through Resolution 1718 is “losing its relevance” and is “detached from reality”.

18 years ago, the UN Security Council unanimously passed Resolution 1718, sanctioning North Korea after her October 9th denotation of a nuclear weapon which represented the first time a nation had withdrawn from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and succeeded in acquiring the bomb.

Resolution 1718, and the follow-on resolution 1874 in 2009 which established a so-defined “Panel of Experts” to conduct credible, fact-based, independent investigations of Pyongyang’s weapons programs and sanctions evasion efforts, were all in the name of preventing North Korea from becoming a nuclear power. As the resolution was required to be renewed every year, and every few years the DPRK tested more ballistic missiles and developed new weapons, stricter and stricter sanctions were added.

US policymakers, lawmakers, and spokesmen would never define them this way, but sanctions are a deterrent, not a punishment mechanism. The history of their unilateral use has shown rare success as a deterrent, but no success as a punishment, if the goal is coercing a regime to change its behaviors.

For this reason, the Chinese and Russian representatives point out that 18 years after becoming a nuclear power, sanctions to prevent them from becoming nuclear power have no more relevance, and for the first time since the late-stage Bush Jr. Administration, the DPRK is set to breathe a little easier on the world stage.

Stating the obvious

Recent years have made clear, the Russian delegation added, that sanctions have neither achieved the international community’s stated aims nor normalized the situation on the Peninsula, adding that they have also not encouraged dialogue.

Noting that it is the only country where open-ended sanctions have been applied by the UN Sec. Council and with no provisions to alter the restrictions imposed whatsoever, the delegation stressed that it is “high time” for the Council to update the sanctions regime.

According to a UN press release on the vote, statements made in the council chamber recount a sort of “Emperor’s new clothes” scenario where each delegation apart from China took turns to stress how important the panel of experts is for the goal and policy of non-proliferation, without ever addressing the fact that Pyongyang already has nuclear weapons and delivery systems.

The United States delegation, which recently cast three stand-alone vetoes in two months over the genocide in Gaza, criticized the Russian delegation for “silencing an independent investigation” and made several additional arguments without ever addressing whether or not sanctions or the panel of experts had, over the previous 18 years, done anything to curb the DPRK’s nuclear weapons program.

One look at the last decade and a half of news headlines will show that the totalitarian dictatorship has in fact not been coerced into changing or abandoning its nuclear program

China’s delegation, which abstained from the vote, revealed that in cooperation with the Russian Federation, Beijing had submitted draft alterations to Res. 1876 that would have “adjusted the sanctions against the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the humanitarian and livelihood field,” noting that the sanctions have had “serious negative impacts on the humanitarian situation on the ground”.

The delegation from China also highlighted that sanctions are supposed to serve to resolve a political issue, but did not go so far as to point out that no nation has made concerted efforts to resolve it since the sanctions were instituted. Apart from presidents Donald Trump and Moon Jae-in and their brief Panmunjong Summit, not one head of state from France, Japan, the UK, and the US—all permanent members of the Sec. Council, and all outspoken critics of Russia’s vote, has ever made a concerted effort to aid in either reconciliation between the Koreas or denuclearization of the peninsula in the 18 years since the sanctions were passed.

Pyongyang has admitted its nuclear weapons policy is defensive in nature and routinely cites Libya, when Moamar Ghaddafi relinquished his chemical and bioweapons in 2003 in exchange for security guarantees but was destroyed by the subsequent administration in Washington, as an example of why the DPRK needs such weapons, and why they can never trust any promises the US or the West more broadly might make to them.

Now that the DPRK stands to be free from the multilateral sanctions (unilateral ones from the US will most certainly remain) it stands to join a coalition of blacklisted states that have no choice but to entwine economically to escape the pressure of a US sanctions regime and the Western World’s complicity in its enforcement.

Joseph Terwilliger, a neuroscientist who accompanied Dennis Rodman on six “basketball diplomacy” trips to the DPRK, points out how this similar pattern has characterized sanctions regimes on Russia, Iran, the DPRK, Cuba, and China. WaL

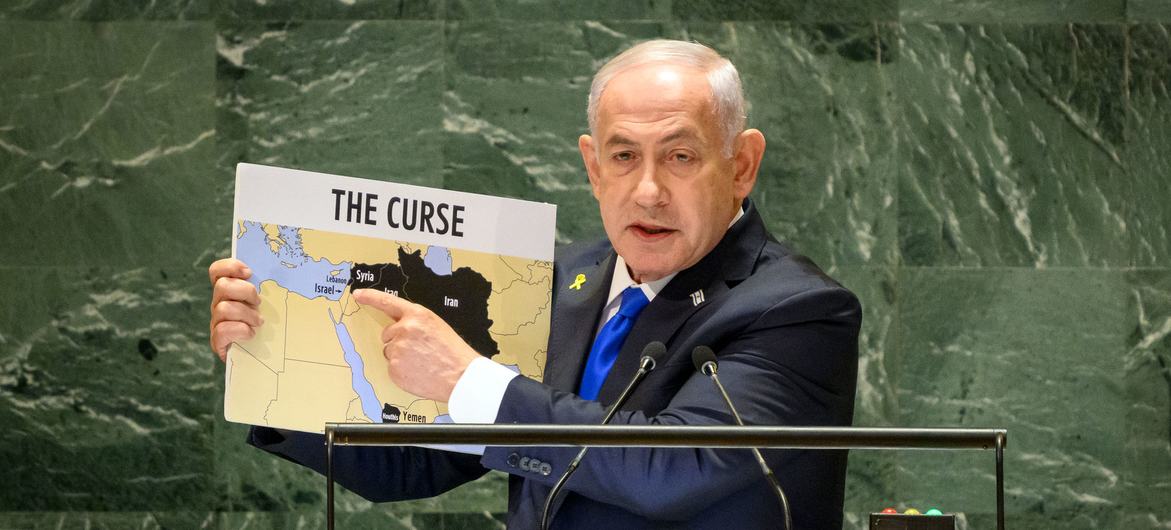

PICTURED ABOVE: The United Nations Security Council Chamber in session.