In Northern Italy, every year between May and June, the forests are alive with the humming of bees. Forest paths are, for a few days, intensely cloaked in white petals and a rich perfume swirls around that’s even stronger than the smell of decaying wood and leaves so typical of semi-dry woodland.

Those effects are caused by the Robinia pseudoacacia, a purely invasive species originally from North America, but that’s nevertheless one of the most recognizable in Italy. Known locally as simply the acacia, it is the single greatest arboreal contributor to the nation’s honey industry. When a particularly aggressive border between a field and a wood is trimmed back, the field is dotted with juvenile acacia trees in less than a year’s time.

Introduced in Italy, and then the rest of Europe in 1662 from the Orto Botanico di Padova, the acacia grows everywhere across Italy, but particularly in the north, in Lombardy, Veneto, Tuscany, and Piedmont where there’s an 85,000-hectare woodland of nothing but acacias.

Invasive plant species can cause massive problems to ecosystems around the world, but exactly which environments are the most vulnerable to them and which aspects of human society contribute greatest to their spread, are two questions that have lacked uniform answers for scientists. Certainly in this case the cause was agricultural, and not to the nation’s overall detriment, but the “God Tree” invaded nearly the whole world out of Korea, Formosa, and China, damaging underground forest environments with long-reaching runners.

Now, a large, multinational analysis of invasive tree species diversity around the world has put greater clarity on the conditions in which invasions happen, and the authors believe it could serve in new international guidelines for how to control for and defend against invasions by non-native trees.

Oneth by Land Twoeth by Sea

Invasive trees must have some adaptation to the climate they end up in for them to propagate in a problematic way. Some hypotheses state that the more diverse an ecosystem is in terms of species richness and composition, the more difficult it is for invasive trees to conduct their invasions because more diversity means the ecosystem is extensively subdivided into niches which are all filled by natives.

Other scientists disagree, arguing that a rich and diverse ecosystem could mean that it’s just easier to get by for a tree, and that invasive species can flourish as the natives do because of the agreeable conditions; and going further to point out that less diverse areas may indeed show that a much smaller selection of species can survive and therefore be harder to invade.

In order to clarify this as much as possible, a Swiss-led study team worked with scientists on 4 other continents to combine global datasets of local-scale forest inventories, the native density and diversity of those inventories, and climate variables along with anthropogenic drivers.

They identified that, excluding monocrop silviculture of species like Scots pine and spruce, the number-one anthropogenic driver was maritime shipping ports, and that vicinity to international ports placed forests at the greatest risk of invasions both across a global average, and when separated by tropical and temperate zones.

However the risk was only of incidence of invasion. After invasive species entered an ecosystem, by measuring a variety of ecological factors the scientists determined that native biodiversity was the largest factor in the severity of those invasions.

“We found that native biodiversity can limit the severity or intensity of non-native tree species invasions worldwide,” says Camille Delavaux, lead author of the study, published in Nature. “This means that the extent of invasion can be mitigated by promoting greater native tree diversity”.

The findings have direct relevance for efforts to manage ecosystems in the fight against biodiversity loss across the globe, says co-author and professor at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, Thomas Crowther.

“By identifying regions that are most vulnerable to invasion, this analysis is useful for designing effective strategies to protect global biodiversity,” said Dr. Crowther.

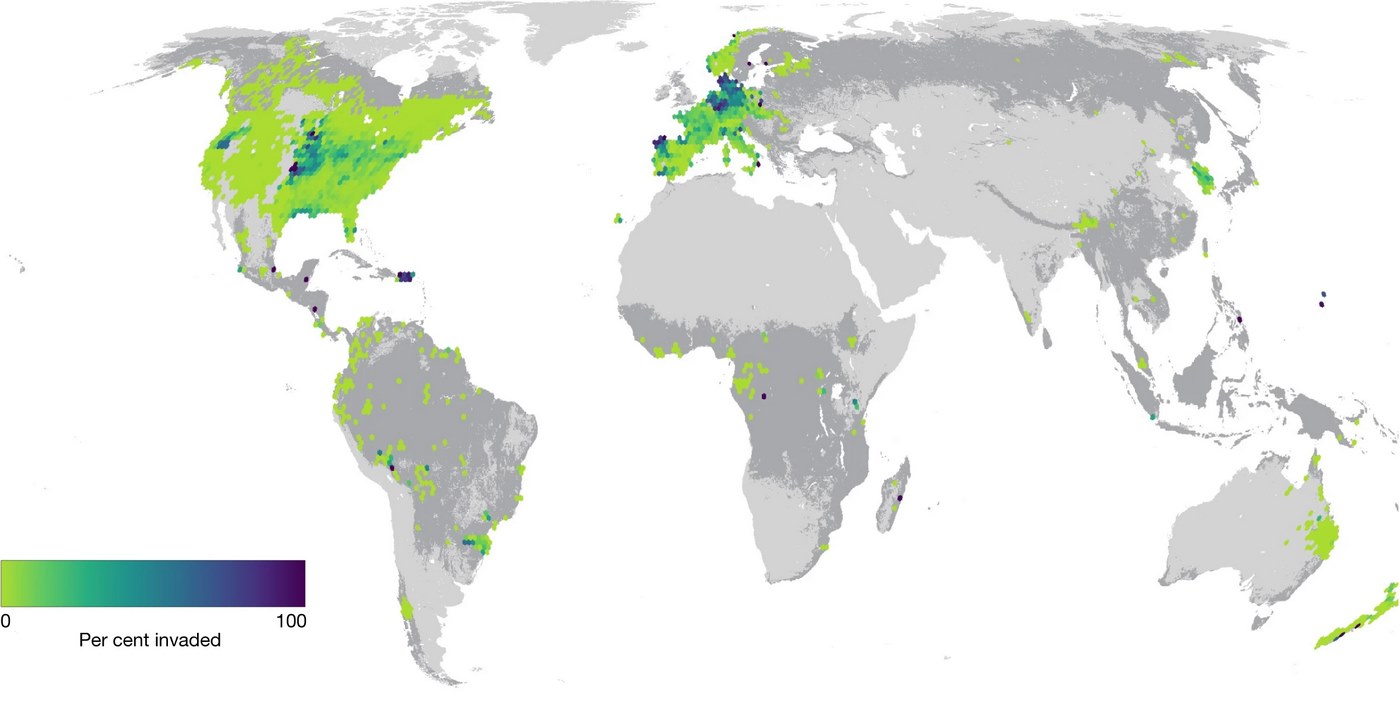

Impact measurements on a global scale show that much of Africa, East Asia, and South America hasn’t been overwhelmed nearly as much as North America and Europe by invasive tree species. Human population density was not consistently correlated with the presence of invasives, but it was correlated with the probability of invasion events.

One key goal of the global biodiversity framework adopted at COP 15 in Montreal in 2022 is to prevent the establishment and spread of potentially invasive species. This global analysis of non-native tree species aims to contribute to the findings of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), which is expected to highlight the substantial impact of invasive species on biodiversity loss in their upcoming status report.

“This global understanding of non-native tree distributions can help countries to prioritize decision making in efforts to halt and reverse the loss of biodiversity,” Crowther emphasizes. WaL

PICTURED ABOVE: The incredible invasive acacia or black locust tree. PC: CC 3.0. (left) Andreas Rockstein (right) Archenzo