Image by David Mark.

For many years the argument for reducing animal agriculture in the U.S. and the world has been based on remarkably flawed science. While it is true that grazing ruminants such as bison, cows, and sheep produce hundreds of tons of methane (CH4) which has a much higher potential to warm the planet, the article titled Scrutinizing The Conversation On Livestock Emissions Reveals A Devastatingly-Flawed Ideological Foundation, published here at World at Large details the extent to which that potential is limited and even negligible in the United States.

According to the EPA’s U.S. emissions inventory of 1990 – 2016, livestock emissions account for one quarter of all CH4 emissions, which make up 10% of the nation’s greenhouse gas (GHG) inventory. So about 2.52% of all the GHGs in the U.S. are from animals.

There’s a sense that, even if the common climate change predictions for 2 degrees celsius of warming are half as dire as many scientists suggest, making every attempt to prevent such warming is warranted. So with that in mind, is removing cattle from the economy, or significantly reducing the presence of animal agriculture in the economy worth the economic destabilization that would come as a result?

It’s hard to say if reducing the nation’s GHG emissions by half of 2.52% would either be worth the collapse of several important economic sectors, or make any meaningful change in the warming of the planet.

Photo by Benjamin Bousquet

Sacred Cow

A broad-examination of this question was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences by Robin White and Mary Beth Hall. They begin their paper’s abstract thusly.

“The US livestock industry employs 1.6 × 10 (to the power of 6) people and accounts for $31.8 billion in exports. Livestock recycle more than 43.2 × 10 (to the power of 9) kg of human-inedible food and fiber processing byproducts, converting them into human-edible food, pet food, industrial products, and 4 × 10 (to the power of 9) kg of nitrogen fertilizer”.

“In the present system, domestically produced, animal-derived foods provided 24% of the energy, 48% of the protein, 23–100% of the essential fatty acids, and 34–67% of essential amino acids available for human consumption in the United States. More than 50% of the food-derived Ca; vitamins A, B12, and D; choline; and riboflavin were from animal products”.

The Economic Research Service in partnership with the USDA detailed the value of animal byproducts from animal agriculture. 10% of the value of a cow is in the byproducts which account for 44% of the live weight of the animal. The byproducts, inedible and edible, of a cow go into making adhesives, ceramics, cosmetics, fertilizer, germicides, glues, candies, refining sugar, textiles, upholstery, photographic films, ointments, paper, heart valves, fashion, lubricants, plastics, and a slew of pharmaceuticals and supplements coming from the glands of the animal such as the adrenal, parathyroid, pituitary, and thyroid.

Among these pharmaceuticals are epinephrine, estrogens, progesterone, insulin, trypsin, parathyroid hormone, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), somatotropin, thyroid stimulating hormone, testosterone, thyroxin, and thymosin, as well as an assortment of serums, vaccines, antigens, and antitoxins.

According to Frank Mitloehner, professor and air quality specialist at the University of California – Davis, and the former chairman of LEAP, a global United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) partnership project to benchmark the environmental footprint of livestock production, there are 90 million head of beef cattle and 9 million dairy cows in the United States.

Beyond this, it’s hard to quantify the cultural value of animal agriculture in the United States. For many it’s a family business and part of their heritage, such as the Noh family and their sheep who graze in a National Forest.

Beef or Leaf?

White and Hall in their paper point out that they agree with several other published works concluding that not only is animal agriculture’s presence in the modern diet worse for the environment, but that plant-based diets have less of an environmental impact and less direct costs of the consumer.

While White and Hall move to make a very strong case for the nutritional inadequacy for plant-based diets, they bring up the flaws with using life-cycle assessments in the discussion over climate change and animal agriculture.

In part 1 of this piece, the foundation of so many theories on climate change and animal ag was found to be immensely flawed. Livestock’s Long Shadow, a report published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) concluded that animal agriculture contributed to 18% in CO2 equivalent of the global GHG emissions.

Remarkably, they claimed that 18% was greater than that of the transportation sector. However in order to reach this conclusion, they measured emissions from transport as only what comes out of the tailpipe, and not what’s produced throughout the breathtaking industrial and economic ecosystem in which transportation and the manufacturing exist in.

In an apples to oranges comparison, they used a far more expansive, cradle-to-grave life-cycle assessment for animal husbandry.

Read part one of this peace to see their mistake — Scrutinizing The Conversation On Livestock Emissions Reveals A Devastatingly Flawed Ideological Foundation.

White and Hall remark that as much as the life-cycle assessments on the environmental impacts of different food production systems suggest that favorable environmental impacts can be more easily achieved through plant-based foods, they are making their calculations based on the current food systems available.

Those life-cycle assessments would no longer therefore be accurate in an agricultural system void of half or all of its ruminant livestock. As they calculate earlier in the piece, a substantial portion of America’s amino acids, fatty acids, lysine, choline, and B12 come from animal-based foods and would need to be replaced.

Manure production and management from livestock was found to be more GHG intensive than synthetic fertilizer production. However the ramp up of synthetic fertilizer production cut into the projected reductions in GHGs that would come as a result of the removal of animal agriculture.

Many consumers prefer organic products, but practicing organic farming (by culture and by law) requires the use of manure or animal products as a way to restore nitrogen in the soil.

If half, a third, or two thirds of all animal agriculture disappeared, organic and regenerative farming practices would likely follow.

Land Use

White and Hall duly point out the problem with assuming that every acre of land required for ruminant animal production is an acre of land that could be furnished with crops. “Removal of animals from the agricultural system removed 168 × 10 (to the power of 6) hectares of nontillable pasture and rangeland from food production”.

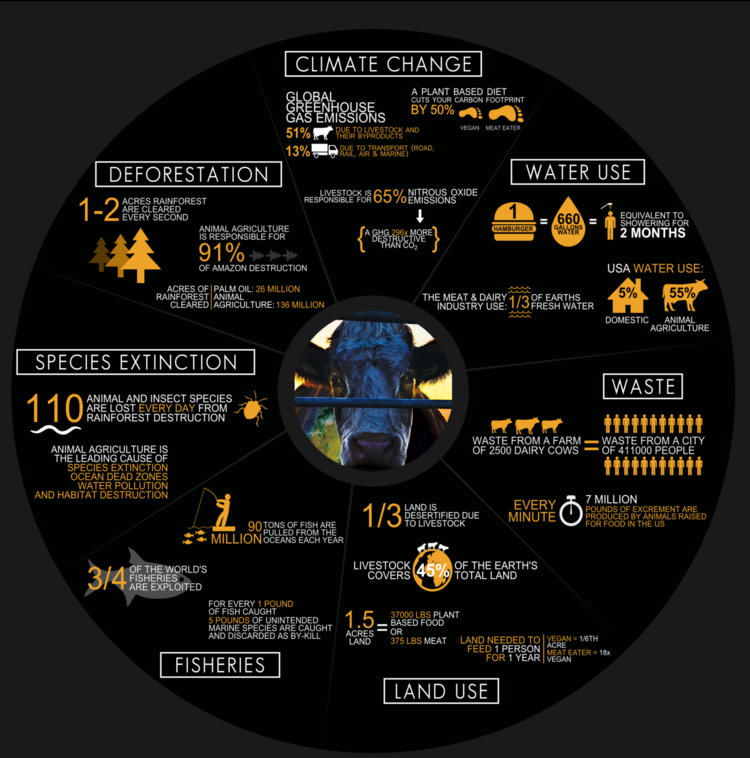

In summary, livestock in America take human-inedible food and convert it into high-energy nutrient-dense food on land that can’t be farmed. The incredibly dishonest Cowspiracy infographic suggests that incorporating meat into the human diet requires 18x more land than if that diet contained only plant-based foods.

PICTURED: The infographic on the website of the widely-discredited Cowspiracy documentary.

However the land used in the United States for ranching and pasturing animals cannot be grown on for a number of reasons. If you did attempt to grow on non-arable land you’d encounter a number of problems, there’s very little soil aggregation – meaning the soil isn’t glued together effectively by water and microbes. This kind of soil (often sandy and rocky) has very little water retention, so along with not providing crops with the water they need to live, it’s very susceptible to erosion and runoff, which cause ecological problems of its own.

Imagine for a second where cattle ranching in the United States flourishes. If you can’t imagine it, here’s a resource from the USDA breaking down land-use state by state. In terms of cropland, you can see states like Ohio, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Georgia, North Dakota use 2-5 times more land for cropping as for rangeland and pastureland.

By contrast, and by measuring in thousands of acres, the mountain and southwest regions, consisting of states like Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, and California provide 326,000 thousand acres of range and pastureland where cattle can flourish but kale cannot.

These are dry, arid states, often covered in 2 things – desert and public land. Utah, for example, is 60% public land, 90% of which is open for cattle grazing. Of the 636 million acres of public land in the United States, 155 million of them are managed for grazing by the Bureau of Land Management.

Any discussion that involves converting livestock grazing land into farmland to feed people would involve cutting into our public land system that manages National Forests, National Riverways, Preservation Areas, and more besides.

PICTURED: Nibepo – Aike Ranch, El Calafate, Argentina. Photo Credit Alex Proimos CC 2.0.

The Farmer’s Gamble

Another significant reason as to why converting the U.S. agriculture model into one of much greater dependance on plant-based foods is the problem with farmers, farm subsidies, and the variations between different crops.

In their model, the removal of animal agriculture resulted in a 23% increase in the total amount of food produced, which may seem ideal, but what, if not meat, would end up on your plate in that 23% increase?

“Grain comprised the majority of the increase, of which corn grain accounted for 77%; 92% of the legumes were comprised of soybeans and soy flour. The dramatic increases in grain and legume production rather than in other crops reflect the allocation of tillable land based on current proportions of crops grown,” White and Hall’s model explains.

It’s unlikely many Americans would accept sitting down to eat a bowl of field corn, soya, or wheat for dinner.

After receiving academic replies (criticisms) of their model, White and Hall issued a paper further detailing the sensitive nature of food-production systems in the United States. For example, as critics suggested that producing nuts, fruits, and vegetables would be far more beneficial in a country without livestock, White and Hall reminded them this may not be economically viable for farmers.

Addressing land use first, White and Hall replied thusly.

“If it were economically desirable to grow higher value crops, it is unlikely that the United States would be importing 51% and 39%, respectively, of the fruits and vegetables we consume”.

They point out that 70% of fruits and vegetables need to be irrigated with fresh water, and concerns about the availability of water for this purpose are increasing. Furthermore, food waste during production, storage, and transport is much higher in fresh produce than in any other food system including animal husbandry.

“Impact and uncertainty of climate, soils, water availability, harvest reliability, and so forth make fruits and vegetables more risky to produce than grains, and this is likely a significant expansion barrier.”

“Feasibility challenges aside, we updated our analysis to calculate conversion of all tillable forage land to fruits and vegetables: the food supply was still insufficient to meet domestic requirements for vitamins D and B12, and specific fatty acids. In this updated scenario, greenhouse gas emissions increased 13% above current GHG emissions even without including GHG emissions from replacing fertilizer (with synthetic equivalents)”.

“This additional scenario […] suggest(s) that not only would expanding fruit and vegetable production be a notable political, economic, and biological challenge, it would fail to generate a food supply capable of meeting the US population’s needs and fail to reduce GHG emissions,” concludes the first section.

Farm Subsidies

One of the most significant barriers to increased fruit and vegetable production would be the economic incentives to farm predictable, multi-use grains and legumes like wheat, corn, and soya provided by a section of the American welfare system collectively known as farm subsidies.

20 billion dollars are given to farmers every year to subsidize different crops, with 80% of all subsidies going towards the production of corn, wheat, soya, cotton, and rice. The Price Loss Coverage program provided a 3.2 billion dollar cushion for American farmers in 2017 if price fluctuations drop the price of crops below a (high) national reference price, set by congress.

The Agricultural Risk Coverage program provided another 3.7 billion in the same year, subsidizing farmers if their revenue per acre falls below a benchmark or guaranteed level.

With these kinds of financial incentives, why would a farmer risk the far more economically unstable market of fresh produce when monocropping grains or legumes provides guaranteed income from Uncle Sam?

With all this taxpayer money going into our food production systems, surely they would be doled out to the most efficient and nutritious food sources considering the heart disease and obesity rates in our country.

In Iowa and Nebraska, the two largest corn-producers in the United States, 50% of all the corn grown is turned into fuel additives in the form of bioethanol. Close to 17% of the corn from these two states is turned into high-fructose corn syrup for use in processed and packaged foods as a sweetener.

Only 5% of the corn grown in the two largest corn producers in the country goes to cattle feedlots.

If in the interest of cutting back on the 2.5% of U.S. emissions from the livestock industry, someone were to replace the National Forest land that produces pasture for the creation of nutrient-dense beef production with semi-arable land void of animals and biodiversity for growing plant-based foods, there’s no suggestion that the farmer managing that land would choose to do anything other than grow corn or soya to be turned into non-nutritious compounds for processed foods or fuel additives for the petrochemical industry.

Photo by Sergiu Vălenaș.

Companion Animals

Beyond all of this, there are aspects of the ruminant-livestock-as-GHG-emitters debate which don’t get brought up.

There are 9 million horses in the U.S. (ruminant livestock) that live longer than cattle and sheep, and therefore produce more methane than their barnyard compatriots, and which are never consumed. No one mentions how the removal of the horse from the American farm or pasture would be very beneficial indeed to the reduction of methane emissions in this country.

There are 170 million dogs and cats in the United States which rely on animal byproducts mostly for kibble and wet food. It’s safe to assume that very few Americans would be willing to put Spike and Fluffy to sleep in order to reduce the 2.5% of total U.S. emissions caused by animal agriculture.

However valuable these animals are in our lives, this is just another example of the breadth of the conversation surrounding livestock and emissions. If the United States wants to address global climate change, it should take appropriate action in the correct course.

And while it’s clear that methane from ruminant livestock is a potent GHG, the conclusion of this debate should have been reached long ago. The warming of the planet is indeed a critical threat, but the farm and the pasture, the farmer and the rancher, the cow and the bison, these are not America’s culprits.

Continue reading on this topic — The Future Of Food Security In America Is Not In Sustainability, But In Regeneration