Tremendous sacrifices have been made in the quest to feed the people of the world, much of it fronted by what was here before we arrived. As recently as the last two decades oil palm production has skyrocketed, as its prolific yield has replaced much of the world’s rapeseed, cottonseed, and sunflower seed production for use as a vegetable oil.

The tragedy which has been outlined for almost as long, has been that oil palm plantations are rapidly replacing tropical rainforest, the most biodiverse habitat on our planet. With such a delicate and important ecosystem in the crosshairs of such a lucrative crop, what is the best strategy to protect the tropics from this resource curse?

Some conservation groups, like the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFR) are willing to take any measures necessary to protect the world’s primary rainforests, but would certainly prefer a zero-expansion/moratorium on oil palm plantation growth and rainforest clearance.

Others, like the Biodiversity and Ecosystem Function in Tropical Agriculture, (BEFTA) think it’s just as important to conduct significant research within the plantations themselves, since oil palm isn’t going away anytime soon, and that because oil palm is a tropical species it’s worth examining what kind of species diversity a plantation can host.

Conflict of Interest

Biodiversity loss is a “complete tragedy,” but “we need to feed the world,” says Edward Turner, a researcher at BEFTA talking with Science. “We need to produce crops that are very productive … in the smallest area possible. And oil palm is the best”.

According to Science, some 90% of the global supply of palm oil comes from Indonesia and Malaysia, where plantations cover 17 million hectares – almost half the area of Germany. Growing demand is pushing the industry into Africa and South America as well.

These are the same tropical regions which are responsible for the world’s coffee production. To someone like Turner, these two crops have the benefit of being able to sustain a little more biodiversity and support a larger number of ecosystem services than a crop like soya, corn, or other temperate agri-products.

There’s no question among the scientific community that conversion of tropical forest to oil palm plantation is a blow for biodiversity and ecosystem health in every conceivable way, as was outlined back in 2011 by Foster et al.

“The huge reduction in tree species diversity will inevitably lead to a comparable reduction in the diversity of animals that use trees, especially the legions of herbivorous insects; plant biodiversity begets animal biodiversity. Not only is diversity reduced at the taxonomic level, but clearly oil palm plantations are architecturally much simpler than forests,” reads the study, explaining the damning effects of biological simplification.

However the study goes on to explain how, for all intents and purposes, things could be worse.

“However, this simplification should not be over-stressed. Oil palm estates, even in the areas away from forest fragments and riverine strips, do contain significant structural complexity, particularly if they are compared with other tropical agricultural crops (e.g. soya bean or rice). The palm trees are large and long-lived, and this provides some heterogeneity and time for a complex assemblage of species to be built up”.

“It’s actually a good crop for conservation, but it just happens to grow in the most biodiverse parts of the world,” Turner told Science.

It’s based on this observation that Edward Turner and his colleagues began researching different collections of wildlife which exist in oil palm plantations, as well as forest management practices and their effect on the capacity to host greater biodiversity in 2014. Four years later, Turner et al. found that soil macrofauna diversity and litter decomposition was higher in specific plots of oil palms where an enhanced management of understory vegetation was applied.

The enhanced method consisted of very minimal use of herbicides, with manual weed removal in a ring around the trees and the walking paths between plots. The policy of Golden Agri-Resources, a part of the massive East and South Asian conglomerate Sinar Mas, is to spray herbicide only in the ring around the trees and along the walking paths. Turner’s research also found that soil fertility was unchanged in both plots treated with and without herbicide, suggesting there is no effect on yield from the competition of the understory vegetation.

Another paper based on the same field work found that the plantations contained 69 different species of dragonfly, including 5 which were as of then unknown in Sumatra entirely. Sumatran barn owls also thrived, as they had a ready source of food in the rodent populations which lived there.

With the help of their oil palm research institute, SMARTRI, Sinar Mas have made sustainability concessions in their plantations equivalent to an area the size of Singapore, a little less than one fifth of all their plantations, thereby meeting the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goal#15 for Sustainable Forests. However Turner hopes he can convince them to adopt the even more enhanced practice of management.

Birds and the Beans

Another crop which features prominently in the tropical landscape is coffee. The coffee bean is only grown in the tropics and commercially available coffee beans really only come from South and Central America, Central Africa, South Asia, and Indo-China.

But responsibly sourced coffee is often a lesser evil than other tropical agribusiness like palm oil because of the perceived better-quality taste found in Arabica beans grown under the shade of a forest canopy, rather than the sunbaked fields that house the lower-quality Robusta species of coffee bean. This is good news for wildlife conservation, as more wildlife can live in a coffee plantation that contains mixtures of trees.

In this case you have an ecological incentive that begets an economic one, as a higher-priced bean due to the quality of the coffee leads companies to create a decent forest cover above their plantations. These intrepid farmers work for the designation of “Bird Friendly” to be stamped on the packaging of their beans so the world knows they’re doing their part to protect tropical bird species.

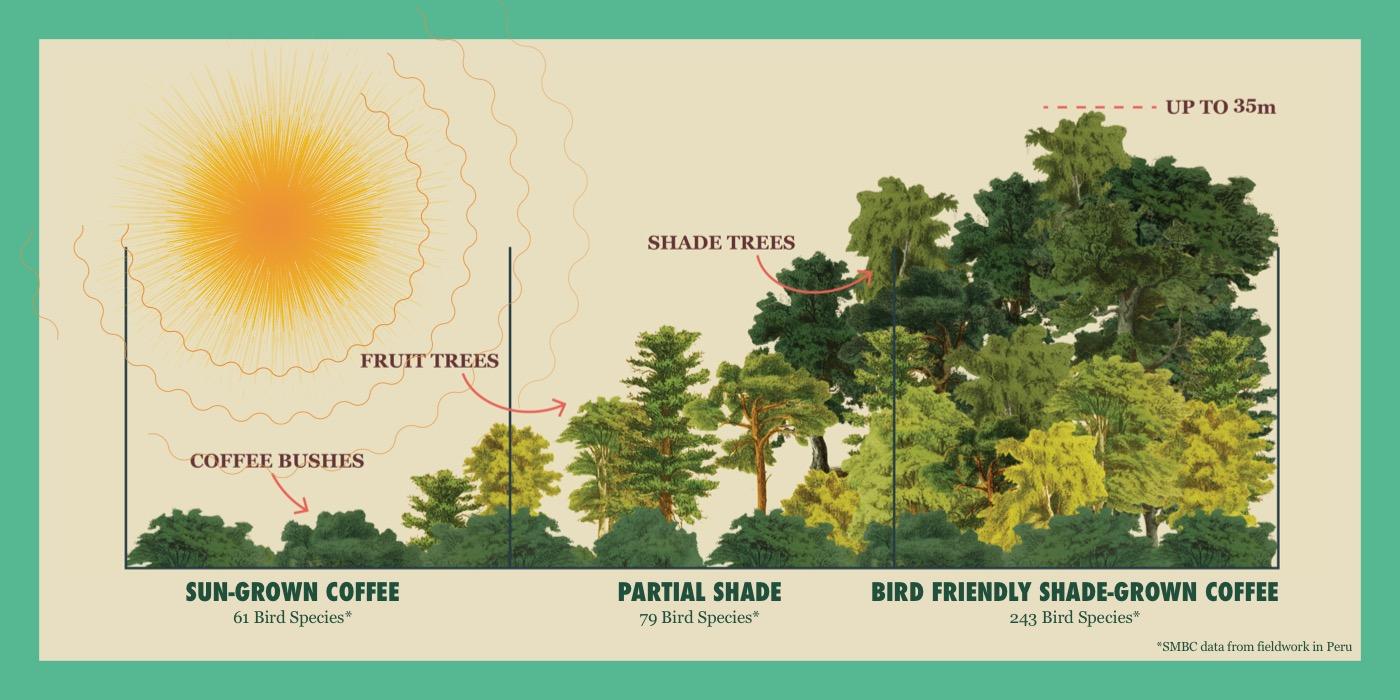

PICTURED: Data from fieldwork done in Peru showing the capacity for shade-grown coffee to support bird species. Photo credit: The Smithsonian Institute.

At 19 million pounds, the total volume of Bird Friendly certified coffee produced has grown by 13 million pounds in the past decade. The number of certified producers participating in the program more than doubled in 2017, with more than 4,600 participants managing farms from Mexico to Colombia and Ethiopia to Thailand. Bird Friendly habitat covers more than 30,000 acres around the world.

Bird Friendly coffee habitat can sustain up to 4 times as many species and as much species volume as sun-grown coffee. Returning to the oil palm however, we find a far grimmer pattern.

At a Loss

In a study published in 2015, a trio of German researchers and their colleagues found that even disturbance-tolerance species are vulnerable from conversion of forests to oil palms. In smallholder Indonesian oil palm plantations the team found that an increase in bird life conditional on the amount of necessary trees to bring back both bird diversity and bird abundance came right along with a loss in revenue for the farmers.

The same is true in Borneo, where not only are most of the bird species there unable to tolerate oil palm habitat, but the small fragmented forest conservations didn’t produce any significant improvement in species abundance and diversity. In fact, compared with contiguous stretches of rainforest, fragments had 60-fold lower abundance of important or threatened bird species.

In Thailand the results are the same. Of the 128 species recorded across all habitats in a paper published in 2006, 84% were recorded in forest, and 60% were recorded only in that habitat; while 15 of the 16 Globally Threatened or Near-Threatened species recorded in the study were found only in forest.

Smallholder farms make up 40% of the oil palm industry, and these farms are far-less equipped with the knowledge and budget necessary to make concessions for biodiversity. Only oil palm giants like Golden-Agri, with their in house research agency can afford to pump money into the research needed to garner the information required for full-scale conservation efforts within palm oil plantations.

PICTURED: Plantation worker watches as a truck unloads freshly harvested oil palm fruit bunches at a collection point.

The story in Science details just how complex and unfortunate the situation is, as well as the many voices which hang on the side of wildlife and think that any cozying up to big palm oil is dangerous, since published papers on the conservation efforts within one of the world’s most destructive crops go some way to legitimize their operations.

“If funding and prestige that comes with access to large data sets lures scientists to a particular direction while ignoring the big elephant in the room, then this is problematic,” Maria Brockhaus, a forest politics expert at the University of Helsinki, told Science.

“The country has the responsibility to ensure independent and critical research to serve the interest of the wider society and not in favor of selected interests”.

Borrowing the language of every published scientist in history, more research is needed to fully understand what the planet is losing in the quest for palm oil and whether it’s capacity to host biodiversity will aid in the conservation of vital species and ecosystem services. But until then Turner’s words still ring out over the struggle to save tropical forest: “we have to feed the world”.