Earlier this March, the unfortunate verdict of an independent “futility analysis” has rendered two promising Alzheimer’s drugs ineffectual at reducing the presence of protein build-ups which are linked with the insidious disease.

Two pharmaceutical partners from the US and Japan that were developing the drug called aducanumab, decided to halt a pair of ongoing phase III trials after the analysis found the drug was unlikely to slow neurodegenerative disease.

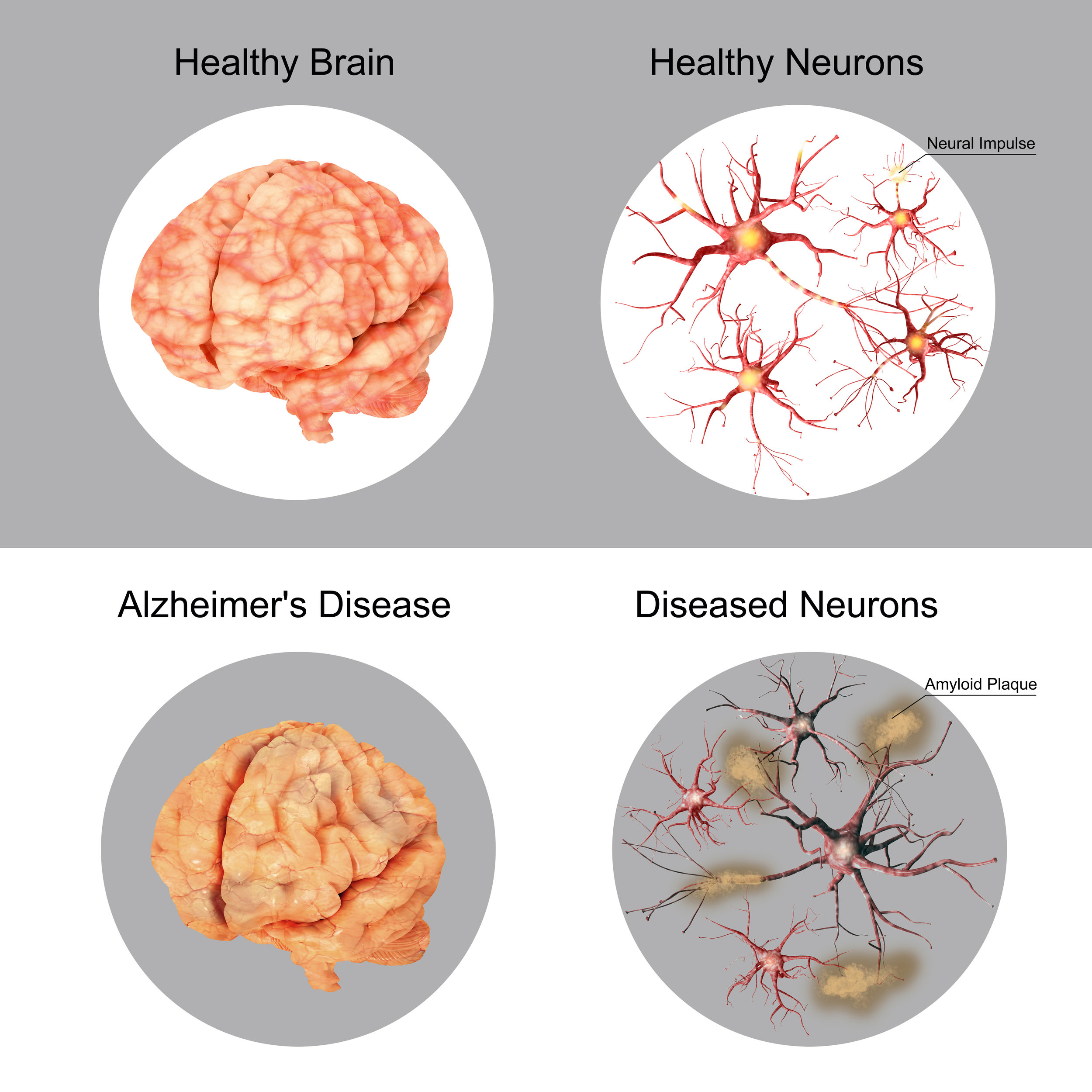

Beta-amyloid is a metabolic byproduct and amino acid that forms into plaques which build up around several parts of the brain like the hippocampus, thalamus, and nearby regions. Higher concentrations of beta-amyloid in the brain are strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease, and many attempts have been made to produce a pharmacological product which can clear away the toxic amyloid. Aducanumab, is one, but solanezumab, gantenerumab, crenezuma, and belenbecestat are all examples of drugs that have failed, are still in early testing, or have been reworked for purposes of sending back for trial.

With nothing on the immediate or semi-immediate horizon, what science can someone turn to if they are concerned about Alzheimer’s? If someone discovers they possess the APOE ɛ4 genetic mutation, placing them at higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, what changes in lifestyle can protect them? One of the only consistently demonstrable pieces of science is sleep.

Sleep Heals the Brain

Sleep is a ridiculously well-selected evolutionary trait that all animals possess. The phenomenon of sleep is characterized by a long period during which the brain cycles through different kinds of slower-brain wave patterns. Each state of sleep has a different pattern of brain activity associated with it, and if they all weren’t absolutely necessary it would’ve strongly been selected against during evolution. The simple fact is that the time spent in a non-useful state of sleep could be better-used by the animal to find food, a mate, or to avoid being eaten by predators.

With that in mind, one particular kind of sleep – slow-wave sleep, characterized by “delta” brain waves, has been discovered as a strong modulator for beta-amyloid, the toxic proteins responsible for Alzheimer’s. In a study of 8 participants, disruption of slow-wave sleep accounted for a 28-30% increase in the levels of beta-amyloid the very next morning.

This was measured by inserting a catheter in the lumbar region of the spine and drawing out a sample of the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid. Cerebral spinal fluid is used by the glymphatic system as a deep-cleaning agent, drawing out the toxic beta-amyloid and other metabolic detritus and removing them from the brain.

Another study found that 17 participants who spent between 5-14 days of sleep monitoring at a sleep research center, had a remarkably higher amount of beta-amyloid in their cerebral spinal fluid after just one night of disrupted sleep. Moreover, this effect was specific for slow-wave sleep disruption, and amazingly showed to correlation with total sleep time, non-REM time, REM time, or sleep efficiency.

Slow Down and Enjoy Life

If beta-amyloid plaque is causally linked to Alzheimer’s, and slow-wave sleep disruption of even just one night is shown so clearly to increase the levels of amyloid in the brain, then the next act is to learn about how to protect from slow-wave sleep disruption.

Slow-wave sleep adds up to about 20% of our total sleep time; diminishing from that figure as we enter the second half of our lives. Most of slow-wave sleep occurs during the first sleep cycle in a chunk lasting about 45-90 minutes. Each cycle of sleep consists of about 6 stages in total and takes about 3 hours. Upon reaching the second cycle, the time spent in slow-wave sleep decreases to make room for an increased appetite for REM sleep – another vitally important component of sleep.

This tells us that slow-wave-optimal sleep will likely occur sometime after sundown and before midnight – relegating late-night shift workers as unfortunate casualties. However genetics can also play a major role in the movement of sleep cycles; a role we don’t fully understand. We do know if you’re an owl, you’ll not have the same requirements as a lark (these are medical terms).

In the second study, slow-wave sleep was disrupted by delivering a tone through earphones to the participant. The amplitude of the tones would progressively increase until delta wave (slow-wave) power decreased, indicating an arousal out of slow-wave sleep.

This suggests another concerning thing regarding how our modern life is affecting our sleep, and that’s that the saturation of noise in our environment could also be disrupting our slow-wave sleep.

If you were to try and wake someone up while they were in deep slow-wave sleep, it would be harder than if you attempted it in any other state. However the study demonstrates that while environmental stimuli may not wake you up all together, it may lift you out of deep sleep and into a lighter state which doesn’t have the power to clear out beta-amyloid.

“In the entire study sample, across the age range of 37 to 92 years, age was negatively and linearly associated with all measures of sleep architecture…”

A Self-fulfilling Prophecy

Right now it looks like a good way to prevent Alzheimer’ is to go to bed between 8-10 pm while trying to avoid all contaminant-noise and wake up with the sun. That’s a tall order for most in this day and age. Sleep is often the first thing to be sacrificed on the dual-alters of career and social relationships, and midnight is usually when we are sending our final text messages, not reaching the end of our first sleep cycle.

However further investigation into the scientific literature deems this proposition all the more important and challenging, as the best time to install this practice of sleep is between ages 20-40. In a population study that excluded participants taking certain medications that disrupt sleep like antipsychotics or antidepressants, 2685 participants, aged 37 to 92 were examined for how things like age, sex, and ethnicity affected their sleep.

“In the entire study sample, across the age range of 37 to 92 years, age was negatively and linearly associated with all measures of sleep architecture other than percentage stage 1,” writes the author of the paper. Percentage stage 1 is classified as non-restorative, and acts sort of like the preparations before a flight takes off from the runway.

“Percentage stage 3-4 (delta, slow-wave) was significantly lower in those older than 54 compared with younger individuals,” the author writes in another passage.

Wrapping up, the unfortunate trend seems indicate that our younger years, when social interactions and technological integration prevent us from going to sleep early, are the most important time to optimize for sleep at the beginning of the night in order to prevent Alzheimer’s later in life.

And unfortunately later in life, when someone is both less-likely to be tempted to stay up late, and more aware of the threat of Alzheimer’s, they are physiologically limited in their powers of intervention because the time spent in the state of sleep which clears away the Alzheimer’s-inducing amyloid plaques reduces with age, becoming almost unobservable after 61.

Not everyone is at great risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases even with a lack of sleep, at not getting adequate sleep throughout life is not tantamount to suicide, but like so many aspects of modern life it just increases the risk. Another interesting aspect of the study is that age-related sleep depth decline was far more negligible in women than in men. Male participants suffered the negative age-related linear association with sleep disruption, while female participants varied far more and didn’t follow the linear curve.

Our bodies have means with which to prevent neurodegeneration without the aid of pharmaceuticals, and as so many other therapeutic mechanisms, sleep is the trigger and guardian.