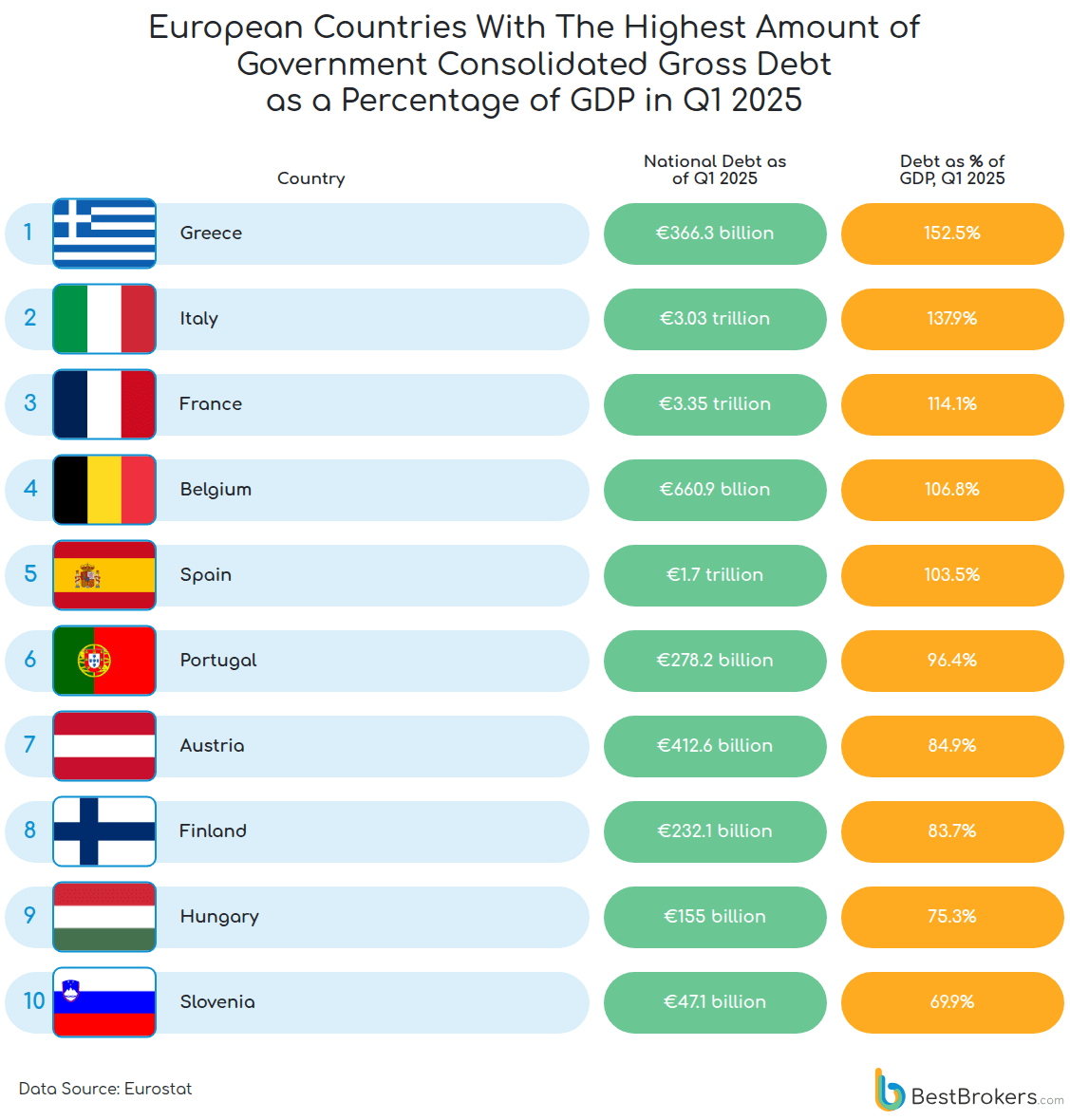

3 of the 5 largest economies in the Eurozone are currently carrying national debts at 100% or more of GDP. When extended to the 10 largest economies, that trend climbs in parity to 6.

Debt-to-GDP ratio is a measure of how much the government owes in borrowed money against the total asset and income values of the private economy in the state it governs, and is often used as a metric to measure risk for investors looking to lend to that country.

The Eurozone though is unique in that in contains several of the world’s largest economies all using the same national currency. Considering each government adopts different spending, financing, and oversight policies, it pays for an investment manager to know how the actions of one country might affect those of a neighbor.

“As debt mounts, fiscal room for maneuver narrows, as the ripple effects spread into monetary policy, inflation, and a country’s long-term competitiveness,” writes Paul Hoffman, data analyst at Best Brokers. “Economists warn that when debt levels push past 100% of GDP, the political space to respond to crises shrinks dramatically”.

A-priory, a large debt burden, whether held by an individual, a corporation, or a government, makes future financial flexibility difficult as the borrower becomes hamstrung by existing demands on their income in the form of debt repayments. If a situation arose where several companies, each engaged in their own separate line of work, were working in sync on a large and complicated project that required long-term financing, but each was overleveraged at the start of the project, investors would recognize that project and those companies by extension as carrying significant risk.

Aside from existing commitments and liabilities, if any immediate debt fulfillment had to be conducted, a given company might cash out of the project, lay off employees necessary for the project’s completion, or sell off assets in its other lines of work that put the operating existence of the company at risk such that it wouldn’t be able to commit to the project.

This is, in effect, the situation with the Eurozone. A default or bailout in one could cause significant downside risk in the others.

Secure at investment grade, earn at junk grade

France (the 2nd-largest EU economy), Italy (the 3rd largest), and Spain (the 4th largest) maintain debt-to-GDP ratios of 114.1%, 137.9%, 103.5% respectively. Their ability to finance that debt relies entirely on the creation of new money by the European Central Bank. That new money drives prices up across the countries in the Eurozone, even in one, for example Estonia, that isn’t heavily indebted. This occurs because the new money chases existing goods, and wasn’t created in response to any commensurate increase in the stock of goods in the country.

To borrow that newly created money, explains Kristoffer Mousten Hansen, a fellow and monetary policy scholar at the Mises Institute in Alabama, Eurozone nations need only offer up their own sovereign bonds as collateral and follow a set of repayment conditions that there’s no indication are ever satisfied.

“Before, when Germany, France, and Italy used their own currencies, their borrowing risks were much more isolated,” Hansen told WaL. “Then, when the euro was created, each participating nation was suddenly able to borrow with the credit worthiness of Germany, the strongest member”.

The old adage about an army moving at the speed of its slowest troop was reversed: the entire bloc, as near as made but little difference, was suddenly as reputable as one of the most reputable countries on Earth. With such a reputation for trustworthiness, German bonds sat almost always near the bottom of the “spread,” a term that describes the variations in yield between the national bonds of the Eurozone countries. Higher risk countries like Greece or Italy gained a significant advantage in the relationship, in that their bonds would have to payout more, but any associated risk of lending to a default-risk country was basically cancelled out by the fact that the interest earned could be spent in other countries, and that Germany’s economy powered the euro’s productivity. In short, investors could secure at investment grade and earn interest at junk bond rates.

This allowed some of the most indebted countries like the three mentioned above, but also Portugal, Greece, Belgium, and to a lesser extent Austria, to enjoy a lucrative way of financing public expenditure, and the strategy was uniform among these profligates: spend now pay later, and the debt-to-GDP ratios averaged across the bloc rose every year until the bloc entered a crisis.

Today, the average debt-to-GDP ratio of the bloc stands at 88%, down from a high of 97% during the COVID years, and of 91% in the wake of the European debt crisis in 2012-2013, when Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain, who together earned the unflattering moniker “PIGS” in reflection of that reliance on deficit spending through new money creation, received bailouts from the ECB. It was 64% in 2007 when the Eurozone reached its current 20-member size, reached 80% two years later, and never returned to below 80% in the 16 years since.

This was despite the fact that, as Hansen notes, there are supposed to be safeguards against overleveraging this distribution of responsibility, with the ECB imposing soft limits of 60% dept-to-GDP ratios across the bloc, and other such austerity measures. But as is the case with many international institutions, their edicts are rarely heeded by national populations, whose governments rarely enact them, and there are few easy or effective ways to force them to do so.

For example, in 2005, Portugal, Germany, and France all exceeded permissible amounts of deficit spending-to-GDP according to the Eurozone’s Stability and Growth Pact, but the Council of Ministers voted against imposing the sanctions that such a breach demanded be incurred.

Hoffman stresses that debt-to-GDP metrics help to compare countries with vastly different sizes and capacities to repay, but that once so many are so high, they not only lose individual value, but reflect a hazardous environment for investors and policy makers.

“The debt-GDP ratio not only shows the fiscal resilience of nations; it also signals future economic growth and sustainability. A high percentage (anything over 70-77%) can undermine investor confidence, leading to higher borrowing costs and reduced fiscal flexibility in crises,” he wrote. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: ECB headquarters in Frankfurt with the twin tower and the historic market hall in the foreground. PC: Epizentrum CC 3.0. BY-SA