A new measure of global mental wellbeing was recently released through a series of papers from Harvard University and Baylor, in which countries like Indonesia and Philippines are suddenly far higher than the European welfare states that are typically considered among the most content.

Every year, the UN Sustainable Development Program, Oxford University, and Gallup publish the World Happiness Report (WHR) with something akin to fanfare, especially by European countries who enjoy high rankings on the index.

Describing itself as “the world’s foremost publication on global wellbeing and how to improve it,” it’s led to an association with the Scandinavian countries as the happiest places on Earth, in particular having Finland rank #1 for 8 years in a row. Yet rich countries fill the top 25 spots, with all but 4 being of non-Euro-Western culture, or 3 depending on how one considers Israel, and 2, arguably 1 of 25 being a middle-income country or lower.

Being published since 2018, the rankings shift around from edition to edition, but it seems that the secret to happiness is being rich and preferably Nordic. If that conclusion is unsatisfying, an alternative in global mindset evaluation has emerged in the Global Flourishing Study (GFS), published not necessarily in direct opposition to the World Happiness Report, but with an understanding by the authors that something different could be done to study human mental wellbeing.

“There’s no single question that can be asked to evaluate well-being. For example, economic indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP) don’t tell us how people in a given country are faring—loneliness, societal division and meaninglessness can be rife even in the richest countries,” the authors wrote in a comment article that accompanied their papers. “All societies need high-quality flourishing data collection, focused on each nation’s and culture’s priorities, throughout the world. Here, we call on countries around the globe to advance this work”.

The World Happiness Report considers GDP per capita, welfare support, freedom, inequality, healthy life-expectancy, perception of corruption, positive emotions, negative emotions, and propensity to donate, volunteer, or help a stranger. By contrast, the GFS opted for a more nuanced approach, particularly as it regarded the measurement of financial wellbeing, which was done subjectively rather than objectively like in the WHR. Dividing the measurements between happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships, and financial stability, it quantified them by thorough definitions and measured them by two questions each.

Character was quantified as volitional wellbeing, defined as the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person’s volitional life are good, and measured by degrees of association between 0-10 for things like “I always act to promote good in all circumstances, even in difficult and challenging situations”.

Additionally, the GFS attempted to measure spiritual wellbeing, specifically by participation in religious institutions and activities. The WHI does not do this.

Tyler VanderWeele, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Director of the Human Flourishing Program which organized the papers comprising the GFS, told WaL that he and his colleagues predicted there would be some differences between their results and those of the WHR.

“There ended up being more differences than anticipated. We think this was due primary to including meaning in life, relationships, and character assessments. It seems the one World Happiness Report question on life evaluation picks up more on financial security than, say, relationships,” he told WaL.

A complicated picture

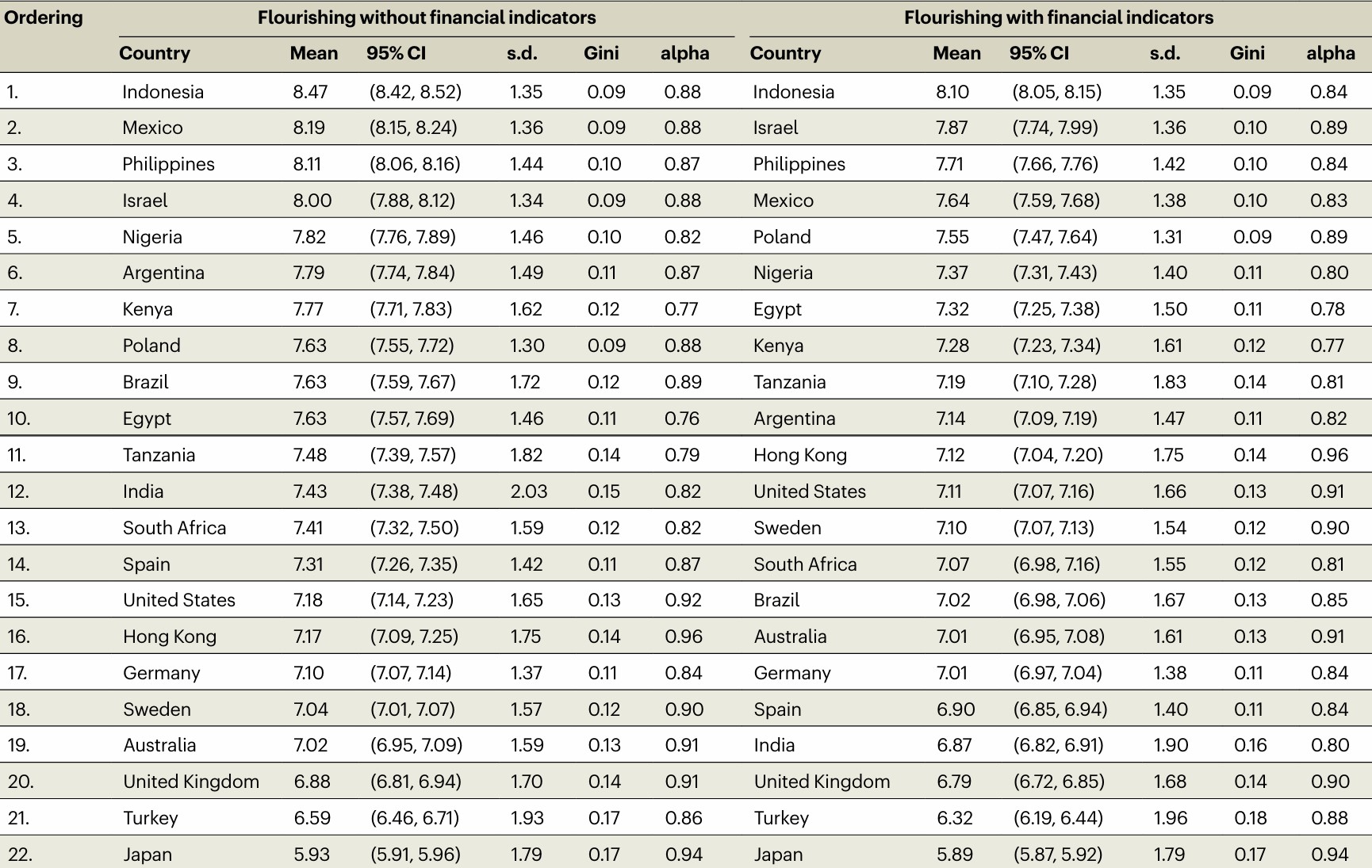

Two rankings were published of the GFS, one in which financial indicators were included, and another where they weren’t. Interestingly, in both indices, the bottom three and the top four are the same. The most flourishing country was Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim nation and second-largest democracy. The least flourishing country was Japan.

By contrast, in the WHR rankings, Indonesia is a dismal 83, while Japan sits 30 places better off.

“Indonesia self-reported highest on many indicators as reported in our flagship paper,” noted VanderWeele. When asked if the spiritual dimension was a key determinant in this, Professor VanderWeele replied that religion isn’t directly included, as there was no single score for it, but that “many aspects of the flourishing index such as meaning in life, good relationships, prosocial are likely powerfully affected by religion”.

A key, he notes, is that the variation across scores means that very little judgment can be drawn conclusively for the vast body of the findings when pooled together.

“Those ordered in the top 5: Indonesia, Israel, Philippines, Mexico, and Poland are considerably higher than others,” he said. “Turkey and Japan are considerably lower than others and these almost certain correspond to meaningful differences”. The UK was also third from bottom on both indices, while numbers 9-20, he continued, “have means right around 7… and we probably shouldn’t make too much of those differences”.

The financial aspect also seems telling. The two questions used to measure financial wellbeing were whether or not the respondent “felt” that they had trouble meeting monthly expenses, were secure in their housing, that they could put food on the table, etc. In other words, it was subjective to the environment the respondent lived in, rather than their place on the UN Human Development Index or GDP per capita rankings.

Rather than place countries on a neat list to be commented on, the GFS and the 22 countries surveyed produced key differences that may be of interest to policymakers within.

The authors found that in countries that include Brazil, Australia, and the US, flourishing increases with age, whereas countries such as Poland and Tanzania see flourishing decrease with age. Some countries, including Japan and Kenya, see a more U-shaped pattern of flourishing with age, in which wellbeing drops and rises throughout a person’s lifetime. However, when VanderWeele and colleagues pooled these responses across all 22 countries, they observed that measures of flourishing for people 18–49 years of age were essentially flat before increasing later in life. This may indicate that—compared with the results of previous research in this field—many younger people across the world may now be worse off than they were in previous generations.

According to the survey responses analyzed by the authors, many countries did not see a substantial difference in flourishing across sexes, although the researchers found that men flourish more than women in Brazil, whereas women flourish more than men in Japan. Similarly, married respondents seemed to have higher flourishing than their single counterparts in many countries based on survey responses. Though, in India and Tanzania, it was the reverse. Those with more education reported higher flourishing in most countries except Hong Kong and Australia, in which the results were the reverse. VanderWeele and colleagues also found that respondents who experienced poverty, abuse or poor health in childhood reported low flourishing in adulthood. An exception to this was Germany, in which the authors found that poor childhood health, compared to good health, seemed to predict higher flourishing in adulthood.

Religious service attendance was one of the factors most consistently associated with present or subsequent well-being, across countries and across outcomes. This is consistent with much previous literature focused principally on the West, but now expanded to a broad range of countries. WaL

We Humbly Ask For Your Support—Follow the link here to see all the ways, monetary and non-monetary.

PICTURED ABOVE: Children in Indonesia play musical chairs PC: Ochimax Studio via Unsplash